Note on perfectoid spaces

In this section, we focus on Section 2 in [Sch], following [Hu], [Hu1], and [Hu2]. Moreover, we need to compare Huber's adic spaces with Berkovich's analytic spaces and Tate's rigid analytic spaces. Hence, we will briefly introduce the notion of Berkovich's analytic spaces in §1.3 and the notion of rigid analytic varieties in §1.4.

§1. Adic Spaces

Definition 1.1. A morphism $f:X\rightarrow Y$ of adic spaces is adic if, for every $x\in X$, there exist open affinoid subspaces $U,V$ of $X,Y$ with $x\in U$ and $f(U)\subset V$ such that the ring homomorphism $\mathscr{O}_{Y}(V)\rightarrow\mathscr{O}_{X}(U)$ of $f$-adic rings is adic.

§1.1. Morphisms of finite type.

The material can be seen in [SP] and [Hu1].

First, we review the definition of morphisms of schemes of finite type/presentation (see [SP], Definition 29.15.1, Lemma 29.15.2, and Definition 29.21.1, and Lemma 29.21.2).

Definition 1.2. Let $f:X\rightarrow Y$ be a morphism of schemes.

- We say that $f$ is locally of finite type if, for all affine opens $U,V$ of $X,Y$ with $f(U)\subset V$, the ring map $\mathscr{O}_{Y}(V)\rightarrow\mathscr{O}_{X}(U)$ is of finite type.

- We say that $f$ is of finite type if it is quasi-compact and locally of finite type.

- We say that $f$ is locally of finite presentation if, for all affine opens $U,V$ of $X,Y$ with $f(U)\subset V$, the ring map $\mathscr{O}_{Y}(V)\rightarrow\mathscr{O}_{X}(U)$ is of finite presentation.

- We say that $f$ is of finite presentation if it is quasi-compact, quasi-separated, and locally of finite presentation.

Compared with the above definition, we reach to the case of adic spaces.

Definition 1.3 ([Hu1, Definition 1.2.1]). Let $f:X\rightarrow Y$ be a morphism of adic spaces.

- We say that $f$ is locally of finite type if, for every $x\in X$, there exists open affinoid subspaces $U,V$ of $X,Y$ with $x\in U$ and $f(U)\subset V$ such that the ring homomorphism $(\mathscr{O}_{Y}(V),\mathscr{O}^{+}_{Y}(V))\rightarrow(\mathscr{O}_{X}(U),\mathscr{O}^{+}_{X}(U))$ of affinoid rings is topologically of finite type.

- We say that $f$ is of finite type if it is quasi-compact and locally of finite type.

- We say that $f$ is locally of finite presentation if, for every $x\in X$, there exists open affinoid subspaces $U,V$ of $X,Y$ with $x\in U$ and $f(U)\subset V$ such that the ring homomorphism $(\mathscr{O}_{Y}(V),\mathscr{O}^{+}_{Y}(V))\rightarrow(\mathscr{O}_{X}(U),\mathscr{O}^{+}_{X}(U))$ of affinoid rings is topologically of finite type and, if the topology of $\mathscr{O}_{Y}(V)$ is discrete, the ring map $\mathscr{O}_{Y}(V)\rightarrow\mathscr{O}_{X}(U)$ is of finite presentation.

Then $\{\textrm{morphisms locally of finite presentation}\}\subset\{\textrm{morphisms locally of finite type}\}\subset\{\textrm{adic}\newline\textrm{morphisms}\}$.

§1.2. Unramified, smooth, and étale morphisms.

For definitions of morphisms of finite type and finite presentation, see §1.1.

First, we review the notions of unramified, smooth, and étale ring maps (see [SP], 10.138, 10.148, and 10.150, and 10.151).

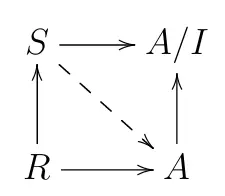

Definition 1.4. Let $R\rightarrow S$ be a ring map. We say $R\rightarrow S$ is formally smooth/formally unramified/formally étale or $S$ is formally smooth/formally unramified/formally étale over $R$ if for every solid commutative diagram

where $I\subset A$ is a square zero ideal, there exists at least one/at most one/a unique dotted map $S\rightarrow A$ making the diagram commute.

The definitions of smooth and étale ring maps make use of the naive cotangent complex, but we will simplify this.

Definition 1.5. Let $R\rightarrow S$ be a ring map.

- We say $R\rightarrow S$ is smooth/étale or $S$ is smooth/étale over $R$ if $R\rightarrow S$ is of finite presentation and formally smooth/formally étale.

- We say $R\rightarrow S$ is unramified or $S$ is unramified over $R$ if $R\rightarrow S$ is of finite type and formally unramified.

Compared with the definitions above, we reach to the case of adic spaces via changing some arrows.

Definition 1.6 ([Hu1, Definition 1.6.5]).

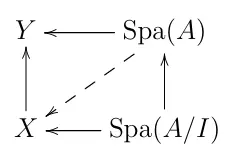

- A morphism $f:X\rightarrow Y$ of adic spaces is unramified/smooth/étale if $f$ is locally of finite type/locally of finite presentation/locally of finite presentation and if, for any affinoid ring $A$, any ideal $I\subset A^{\vartriangleright}$ with $I^{2}=0$, and any morphism ${\rm{Spa}}(A)\rightarrow Y$, the map ${\rm{Hom}}_{Y}({\rm{Spa}}(A),X)\rightarrow{\rm{Hom}}_{Y}({\rm{Spa}}(A/I),X)$ is injective/surjective/bijective.

- A morphism $f:X\rightarrow Y$ of adic spaces is unramified/smooth/étale at a point $x\in X$ if there exist open affinoid subspaces $U,V$ of $X,Y$ with $x\in U$ and $f(U)\subset V$ such that $f|_{U}:U\rightarrow V$ is unramified/smooth/étale.

Note that the second statement of (i) above can be described as follows. For every solid commutative diagram in the following, there exist at most one/at least one/a unique one dotted map making the diagram commute.

§1.3. Berkovich’s analytic spaces.

We will introduce the notion of Berkovich's analytic spaces following [Ber] and [Ber1]. Berkovich's analytic spaces is one of the non-archimedean analogues of complex analytic spaces. The definition of analytic spaces in [Ber1] is more general than the definition in [Ber] (the analytic spaces in [Ber] corresponds to the good analytic spaces in [Ber1]). So we will make use of the definition in [Ber1].

§1.3.1 Underlying topological spaces.

First, we introduce some structures on topological spaces for further use (see [Ber1, §1, 1.1]). All compact, locally compact, and paracompact spaces are assumed to be Hausdorff.

Definition 1.7.

- A topological space is paracompact if it is Hausdorff and every open cover of it admits a locally finite refinement.

- A topological space $X$ is locally Hausdorff if every point $x\in X$ admits an open Hausdorff neighborhood.

Remark 1.8. Note that in [Tam], a paracompact space also requires that the locally finite refinement in (i) above is an open cover.

Let $X$ be a topological space and let $\tau$ be a collection of subsets of $X$ provided with the induced topology. We put $\tau|_{Y}:=\{V\in\tau;V\subset Y\}$ for any subset $Y\subset X$.

Definition 1.9. We say that the collection $\tau$ above is a quasi-net on $X$ if, for every point $x\in X$, there exist $V_{1},...,V_{n}\in\tau$ such that $x\in V_{1}\cap\cdot\cdot\cdot\cap V_{n}$ and the set $V_{1}\cup\cdot\cdot\cdot\cup V_{n}$ is a neighborhood of $x$, i.e. $V_{1}\cup\cdot\cdot\cdot\cup V_{n}$ contains an open set $U\subset X$ with $x\in U$. Furthermore, $\tau$ is said to be a {\rm{net on $X$}} if it is a quasi-net and, for any $U,V\in\tau$, $\tau|_{U\cap V}$ is a quasi-net on $U\cap V$.

Definition 1.10 ([Dug, p255]). Let $X$ be a topological space and $S\subset X$ be a subset. $S$ is said to be locally closed if every point $s\in S$ has a neighborhood $U$ such that $S\cap U$ is closed in $U$.

§1.3.2 The category of analytic spaces.

Throughout, we fix a nonarchimedean field $k$ whose valuation can be trivial. The category of $k$-affinoid spaces is dual to the category of $k$-affinoid algebras (see [Ber, §2.1]). The $k$-affinoid spaces associated with a $k$-affinoid algebra $\mathscr{A}$ is denoted by $X:=\mathscr{M}(\mathscr{A})$.

If for each nonarchimedean field $K$ over $k$, we are given a class $\Phi_{K}$ of $K$-affinoid spaces, the system $\Phi=\{\Phi_{K}\}$ is assumed to satisfy the following conditions:

(i) $\mathscr{M}(K)\in\Phi_{K}$.

(ii) $\Phi_{K}$ is stable under isomorphisms and direct products. In other words, for $X\in\Phi_{K}$, if $X'$ is a $K$-affinoid space with $X\cong X'$, then we have $X'\in\Phi_{K}$, and for $X,Y\in\Phi_{K}$, we have $X\times Y\in\Phi_{K}$.

(iii) If $\varphi:Y\rightarrow X$ is a finite morphism of $K$-affinoid spaces with $X\in\Phi_{K}$, then $Y\in\Phi_{K}$.

(iv) If $(V_{i})_{i\in I}$ is a finite affinoid covering of a $K$-affinoid space $X$ with $V_{i}\in\Phi_{K}$, then $X\in\Phi_{K}$.

(v) If $K\hookrightarrow L$ is an isometric embedding of nonarchimedean fields over $k$, then for any $X\in\Phi_{K}$, one has $X{\widehat{\otimes}_{K}L}\in\Phi_{L}$.

Definition 1.11. The class $\Phi_{K}$ is said to be dense if each point of each $X\in\Phi_{K}$ admits a fundamental system of affinoid neighborhoods $V\in\Phi_{K}$. The system $\Phi$ is said to be dense if all $\Phi_{K}$ are dense.

The affinoid spaces from $\Phi_{K}$ (resp. $\Phi$) and their affinoid algebras will be called $\Phi_{K}$-affinoid (resp. $\Phi$-affinoid).

From (ii) and (iii) above, we deduce that $\Phi_{K}$ is stable under fiber products. In other words, for $X,Y,Z\in\Phi_{K}$ with morphisms $X\rightarrow Z$ and $Y\rightarrow Z$, we have $X\times_{Z}Y\in\Phi_{K}$.

Let $X$ be a locally Hausdorff space and let $\tau$ be a net of compact subsets on $X$.

Definition 1.12. A $\Phi_{K}$-atlas $\mathscr{A}$ on $X$ with the net $\tau$ is a map that assigns, to each $U\in\tau$, a $\Phi_{K}$-affinoid algebra $\mathscr{A}_{U}$ together with a homeomorphism $U\xrightarrow{\sim}\mathscr{M}(\mathscr{A}_{U})$ and, to each pair $U,V\in\tau$ with $U\subset V$, a bounded homomorphism $\mathscr{A}_{V}\rightarrow\mathscr{A}_{U}$ of $\Phi_{K}$-affinoid algebras that identifies $(U,\mathscr{A}_{U})$ with an affinoid domain in $(V,\mathscr{A}_{V})$.

Definition 1.13. A triple $(X,\mathscr{A},\tau)$ of the above form is said to be a $\Phi_{K}$-analytic space.

§1.4. Rigid analytic varieties.

The notion of rigid analytic variety is also one of the nonarchimedean analogues of complex analytic space. It originated in John Tate's thesis, [Tat]. In this subsection, we briefly introduce it following [BGR] and [BS].

§1.4.1 $G$-topological spaces.

As a technical trick, we generalize the usual topology to the so-called Grothendieck topology, [SGA4]. Roughly speaking, a $G$-topological space is a set that admits a Grothendieck topology. We will first introduce Grothendieck topology following the definition in [BS], where the "Grothendieck topology" means the "Grothendieck pretopology" in [SGA4].

Definition 1.14. Let $\mathscr{C}$ be a (small) category. A Grothendieck topology $T$ consists of the category ${\rm{Cat}}(T)=\mathscr{C}$ and a set ${\rm{Cov}}(T)$ of families $(U_{i}\rightarrow U)_{i\in I}$ of morphisms in $\mathscr{C}$, called open coverings, such that the following axioms are satisfied:

- If $U'\rightarrow U$ is an isomorphism in $\mathscr{C}$, then the one-element family $(U'\rightarrow U)\in{\rm{Cov}}(T)$.

- If $(U_{i}\rightarrow U)_{i\in I}$ and $(V_{ij}\rightarrow U_{i})_{j\in I}$ are open coverings, then $(V_{ij}\rightarrow U)_{i,j\in I}\in{\rm{Cov}}(T)$.

- If $(U_{i}\rightarrow U)_{i\in I}$ is an open covering and $V\rightarrow U$ is a morphism in $\mathscr{C}$, then the fiber products $V\times_{U}U_{i}$ exist in $\mathscr{C}$ and $(V\times_{U}U_{i}\rightarrow V)_{i\in I}\in{\rm{Cov}}(T)$.

Remark 1.15. Note that this is slightly different to the definition in [Poon], which requires that a Grothendieck topology consists of the set ${\rm{Cov}}(T)$ only. Moreover, the pair $(\mathscr{C},T)$ is usually called a site. However, to suite our needs in rigid geometry, we stick with the terminology in [BS].

We specialize the definition above to the case that is more suited to our needs. And from now on, we will exclusively consider the Grothendieck topology of such a special type, unless explicitly stated otherwise.

Definition 1.16. Let $X$ be a set. A Grothendieck topology (also called $G$-topology) $\mathfrak{T}$ on $X$ consists of

- a category of subsets of $X$, called admissible open subsets or $\mathfrak{T}$-open subsets of $X$, with inclusions as morphisms, and

- a set ${\rm{Cov}}(\mathfrak{T})$ of families $(U_{i}\rightarrow U)_{i\in I}$ of inclusions with $\bigcup_{i\in I}U_{i}=U$, called admissible coverings or $\mathfrak{T}$-coverings.

Remark 1.17. Note that in this case, the fiber products will come as intersections of sets.

We call $X$ a $G$-topological space and write more explicitly as $X_{\mathfrak{T}}$ when $\mathfrak{T}$ is needed to be specified.

§1.4.2 Presheaves and sheaves on $G$-topological spaces.

The notion of Grothendieck topology defined in § 1.4.1 enables us to adapt presheaf or sheaf to such a general situation.

Definition 1.18 ([BS, 5.1, Definition 2]). Let $\mathfrak{C}$ be a category and let $\mathfrak{T}$ be a Grothendieck topology in the sense of Definition 1.14. A presheaf $\mathscr{F}$ on $\mathfrak{T}$ with values in $\mathscr{C}$ is a functor $$\mathscr{F}:{\rm{Cat}}(\mathfrak{T})^{opp}\longrightarrow\mathfrak{C}.$$

If $\mathfrak{C}$ is a category admitting products, then the presheaf $\mathscr{F}$ is said to be a sheaf if the sequence $$\mathscr{F}(U)\rightarrow\prod_{i\in I}\mathscr{F}(U_{i})\mathrel{\mathop{\rightrightarrows}} \prod_{i,j\in I}\mathscr{F}(U_{i}\times_{U}U_{j})$$ is exact for any open covering $(U_{i}\rightarrow U)_{i\in I}$ in ${\rm{Cov}}(\mathfrak{T})$.

Remark 1.19. Note that the definition of Grothendieck topology assures the existence of the fiber products $U_{i}\times_{U}U_{j}$ in $\textrm{Cat}(\mathfrak{T})$.

Morphisms of presheaves or sheaves are just natural transformations of functors.

Definition 1.20. A morphism of presheaves $f:\mathscr{F}\rightarrow\mathscr{G}$ is a morphism of functors from $\mathscr{F}$ to $\mathscr{G}$. A morphism of sheaves $f:\mathscr{F}\rightarrow\mathscr{G}$ is a morphism of presheaves $f:\mathscr{F}\rightarrow\mathscr{G}$.

Hence, we can define presheaves and sheaves on a $G$-topological space.

Definition 1.21 ([BGR, 9.2.1, Definition 1]). A presheaf $\mathscr{F}$ with values in a category $\mathscr{C}$ on a $G$-topological space $X$ is a contravariant functor $$\mathscr{F}:{\rm{Cat}}(\mathfrak{T})\longrightarrow\mathscr{C},$$ where $\mathfrak{T}$ is a Grothendieck topology on $X$. If $\mathscr{C}$ is a category admitting products, then $\mathscr{F}$ is a sheaf on the $G$-topological space $X$ if it is a sheaf in the sense of Definition 1.18.

The following kind of Grothendieck topology is of special interest to us.

Definition/Proposition 1.22 ([BGR, §5.1, Proposition 5]). Let $K$ be a field and let $X$ be an affinoid $K$-space. Then the strong Grothendieck topology on $X$ is a Grothendieck topology on $X$ that satisfies the following conditions:

$(G_{0})$ $\varnothing$ and $X$ are admissible open subsets of $X$.

$(G_{1})$ Let $U\subset X$ be an admissible open subset with an admissible covering $(U_{i})_{i\in I}$ and let $V\subset U$ a subset. If $U_{i}\cap V$ is admissible open in $X$ for each $i\in I$, then $V$ is admissible open in $X$.

$(G_{2})$ If $\mathfrak{U}=(U_{i})_{i\in I}$ is a covering of an admissible open $U\subset X$ with an admissible refinement such that each $U_{i}$ is admissible open in $X$, then $\mathfrak{U}$ is an admissible covering of $U$.

§1.4.3 Locally $G$-ringed spaces and analytic varieties.

The definition of rigid analytic varieties makes use of the notion of locally $G$-ringed spaces. The so-called $G$-ringed spaces are analogous to our familiar ringed spaces.

Definition 1.23 ([BGR, §9.1.1]). A $G$-ringed space is a pair $(X,\mathscr{O}_{X})$ consisting of a $G$-topological space $X$ and a sheaf $\mathscr{O}_{X}$ of rings on $X$, called the structure sheaf of $X$. A locally $G$-ringed space is a $G$-ringed space $(X,\mathscr{O}_{X})$ such that all stalks $\mathscr{O}_{X,x},x\in X$, are local rings. If the structure sheaf $\mathscr{O}_{X}$ is a sheaf of algebras over a fixed ring $R$, then such a $G$-ringed space $(X,\mathscr{O}_{X})$ is said to be over $R$.

Definition 1.24 ([BGR, §9.1.1]). A map $f:X\rightarrow Y$ between $G$-topological spaces is said to be continuous if the following conditions are satisfied:

(i) If $V\subset Y$ is an admissible subsets, then $f^{-1}(V)$ is an admissible subsets of $X$.

(ii) If $(V_{i})_{i\in I}$ is an admissible covering of an admissible subset $V\subset Y$, then $(f^{-1}(V_{i}))_{i\in I}$ is an admissible covering of the admissible subset $f^{-1}(V)$.

We need appropriate morphisms for $G$-ringed spaces. In fact, we have the following definitions analogous to that of morphisms of ringed spaces and locally ringed spaces.

Definition 1.25 ([BGR, 9.3.1]). A morphism of $G$-ringed spaces $f:(X,\mathscr{O}_{X})\rightarrow(Y,\mathscr{O}_{Y})$ is a pair $(f,f^{*})$ where $f:X\rightarrow Y$ is a continuous map of $G$-topological spaces and $f^{*}$ is a collection $\mathscr{O}_{Y}(V)\rightarrow\mathscr{O}_{X}(f^{-1}(V))$ of ring maps for any admissible open subset $V\subset Y$ that are compatible with restriction maps.

A morphism of locally $G$-ringed spaces $f:(X,\mathscr{O}_{X})\rightarrow(Y,\mathscr{O}_{Y})$ is a morphism of $G$-ringed space $f:(X,\mathscr{O}_{X})\rightarrow(Y,\mathscr{O}_{Y})$ such that all induced ring maps $f^{*}_{x}:\mathscr{O}_{Y,f(x)}\rightarrow\mathscr{O}_{X,x}$ for $x\in X$ are local.

Let $R$ be a fixed ring. An $R$-morphism $f:(X,\mathscr{O}_{X})\rightarrow(Y,\mathscr{O}_{Y})$ of $G$-ringed spaces over $R$ is a morphism of $G$-ringed spaces $f:(X,\mathscr{O}_{X})\rightarrow(Y,\mathscr{O}_{Y})$ such that, in addition, $f^{*}$ is a collection $\mathscr{O}_{Y}(V)\rightarrow\mathscr{O}_{X}(f^{-1}(V))$ of $R$-algebra homomorphisms for all admissible open subsets $V\subset Y$.

Remark 1.26. We follow the convention of ringed spaces that we denote a $G$-ringed space $(X,\mathscr{O}_{X})$ simply by $X$ and we denote a morphism of $G$-ringed spaces by suppressing the morphism of structure sheaves.

In the following, let $k$ be a fixed complete nonarchimedean field. Next, we are in a position to introduce global analytic varieties.

Definition 1.27 ([BGR, 9.3.1, Definition 4]). A rigid analytic variety over $k$ (also called a $k$-analytic variety) is a locally $G$-ringed space $(X,\mathscr{O}_{X})$ over $k$ such that the following axioms are verified:

(i) The Grothendieck topology of $X$ satisfies properties $G_{0}$, $G_{1}$, and $G_{2}$ described in Proposition 1.22.

(ii) There exists an admissible covering $(X_{i})_{i\in I}$ of $X$ with $(X_{i},\mathscr{O}_{X}|_{X_{i}})$ being a $k$-affinoid variety for each $i\in I$.

§2. Almost mathematics

In this section, we focus on Faltings' almost mathematics which first arose in his paper [Hodg], which is the first of a series works on the subject of $p$-adic Hodge theory, ending with [Falt]. The motivating point of $p$-adic Hodge theory can be traced back to Tate's classical paper [Tat1]. We will use Gabber's book [Gab] as a basic reference. The content will be useful in understanding Section 4 in Scholze's paper [Sch].

References

- [BGR] S. Bosch, U. Güntzer, and R. Remmert, Non-Archimedean analysis. A systematic approach to rigid analyticgeometry, Grundlehren der Mathematischen Wissenschaften, Bd. 261, Springer, Berlin-Heidelberg-New York, 1984.

- [BS] Siegfried Bosch, Lectures on Formal and Rigid Geometry, Lect.Notes Mathematics vol. 2105, Springer, Cham, 2014.

- [Poon] Bjorn Poonen, Rational Points on Varieties, Graduate Studies in Mathematics Volume: 186, American Mathematical Society, 2017.

- [SGA4] M. Artin, A. Grothendieck, and J.-L. Verdier, Théorie des topos et cohomologie étale des schémas, Lecture Notes in Math. 269, 270, 305, Berlin-Heidelberg-New York, Springer. 1972-1973.

- [Gab] O. Gabber and L. Ramero, Almost ring theory, volume 1800 of Lecture Notes in Mathematics, Springer-Verlag, Berlin, 2003.

- [Hodg] G.Faltings, p-adic Hodge theory, J. Amer. Math. Soc. 1 (1988), 255-299.

- [Falt] G.Faltings, Almost étale extensions, Astérisque 279 (2002), 185-270.

- [Tat] J. Tate, Rigid analytic spaces, Invent. Math. 12 (1971), 257-289.

- [Tat1] J. Tate, p-divisible groups, Proc. conf. local fields (1967), 158-183.

- [Dug] James Dugundji, Topology, Allyn and Bacon, Inc., 470 Atlantic Avenue, Boston, 1966.

- [Tam] Tammo Tom Dieck, Algebraic Topology, European Mathematical Society, 2008.

- [Ber] V.G. Berkovich, Spectral Theory and analytic Geometry over NonArchimedean fields, Math. Surv. Monogr. vol. 33, Am. Math. Soc., Providence, RI, 1990.

- [Ber1] V.G. Berkovich, Étale cohomology for non-Archimedean analytic spaces, Publ. Math., Inst. Hautes Etud. Sci. 78 (1993).

- [SP] The Stacks Project Authors, Stacks Project. Available at http://math.columbia.edu/algebraic_geometry/stacks-git/.

- [Sch] Peter Scholze, Perfectoid Spaces, IHES Publ. math. 116 (2012), 245-313.

- [Hu] R. Huber, Continuous valuations, Math. Z. 212 (1993), 455-477.

- [Hu1] R. Huber, Étale cohomology of rigid analytic varieties and adic spaces, Aspects of Mathematics, E30., Friedr. Vieweg & Sohn, Braunschweig, Springer Fachmedien Wiesbaden, 1996.

- [Hu2] R. Huber, A generalization of formal schemes and rigid analytic varieties, Math. Z. 217 (1994), 513-551.

0 人喜欢

We apologize that this note has ended halfway because the author had quit mathematics😭😭